Award for Management 2008

Denis Landenbergue

Denis Landenbergue is being recognized for his lifelong interest in wetlands and bird conservation, first as a volunteer and professionally since 1989, and for his outstanding achievements with regard to designation of Ramsar Sites/protected areas together with improved management for many of these wetlands, especially in Africa, South and Central America, and Asia. Since he started working with WWF International in 1999, Denis Landenbergue’s work has led to the designation of 84 million hectares in freshwater protected areas between July 1999 and June 2007, mostly as Ramsar Sites. Mr Landenbergue has also assisted many countries to become Contracting Parties to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. To reach these aims, Mr Landenbergue has collaborated closely with the Secretariat and offered respect and constant support to officials in charge of wetland conservation in developing countries. He has administered many small grants, which in turn have attracted manifold additional funds from international aid agencies and corporate donors. Denis Landenbergue has supported and/or been instrumental in launching several regional wetland conservation initiatives. His success is due to his strong sense of collaboration and partnership, his talent for publicizing, praising and encouraging the achievements of governments, and his dedication.

---Interview with Denis Landenbergue---

Denis Landenbergue, WWF International’s manager for wetlands conservation, is one of three winners of this year’s Ramsar Wetland Conservation Awards, in his case in the "Management" category. Denis is being recognized for his lifelong commitment to wetlands management. During his career he has played a key role in worldwide efforts to designate millions of hectares of freshwater areas as Wetlands of International Importance, and has assisted many countries, particularly developing countries, in joining the Convention on Wetlands.

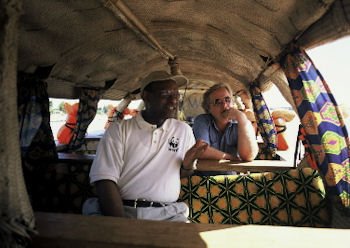

Just back from Africa following a ceremony designating the Ngiri-Tumba-Maindombe area in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as the largest Wetland of International Importance in the world, Denis talks about the successes and challenges of wetland conservation, how he first got involved in wetland issues, and on winning the 2008 Ramsar Wetland Conservation Award.

The Ngiri-Tumba-Maindombe in the DRC will be the largest wetlands area added to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance? What is involved in getting such a large site designated?

Listing the Ngiri-Tumba-Maindombe, an area twice the size of Belgium, is a major accomplishment, not only for the wildlife that live there but also for the welfare of communities who depend on this wetland for their livelihoods. Designating such a wetland is about the sustainable use of its resources. It is about protecting and managing the freshwater habitat to conserve biodiversity and ensure supplies of clean water, food and services for millions of people who depend on the wetlands every day, as well as recognition of the economic, social and environmental value of the wetlands.

What kind of work goes into designating a site such as this or any other site for that matter? A lot of time and patience, and being able to rely on the right people in the right place at the right time. The success of the DRC designation is a result of strong support and excellent coordination among many people, including from the DRC Ministry of Environment, the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation, the Secretariat of the Convention on Wetlands, the WWF network, and local associations.

Most importantly, the designation received the support of more than 30 ethnic groups that live in the area. Consultation with local populations is crucial. You can’t just map out the site in an office, you have to go to the field and listen to people who live there and work with them. They need to see visible action that will improve their livelihoods and overall quality of life.

Support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through their Central African Regional Programme for Environment (CARPE) has also been extremely valuable. Strong interest expressed by the International Commission for the Congo-Oubangui-Sangha Basin (CICOS) is a clear sign that the approach we have adopted deserves replication elsewhere in the Congo river basin.

Despite the scale of the project, it took less than two years to get to the designation stage, although initial work started a few years earlier. The speed reflects the efficiency of the process and exceptional collaboration between government, NGOs, donor agencies and other partners. Considering the importance and the location of the site, I must say this has been a relatively fast achievement. I have seen much smaller sites take up to six or seven years, or even more, to reach the same stage. Results can only happen when you can rely on very committed people. You cannot manage a wetland properly without a great deal of patience and wide cooperation, and of course, without a sufficient level of funding.

Cooperation is a key aspect in listing wetland sites, but what was your specific role in designating the DRC site and other sites?

One of my main roles is to talk with as many people as possible who are involved or have a stake in a wetland area – it is important to understand their concerns and needs, and it helps increase everybody’s motivation to act. In the DRC, as in the many other places where we support similar kinds of projects, I spent a lot of time meeting with officials from the Ministry of Environment and other government agencies, consulting with WWF staff working on the ground, and with donors interested in supporting conservation projects in the area. It is very important to have government support right from the beginning; a government’s decision to undertake the Convention on Wetlands designation of a wetland is a clear indication that the area is a priority on the national agenda.

In addition to technical and scientific support, WWF provided small grants to conduct a biodiversity inventory for the area. The Ngiri-Tumba-Maindombe Ramsar Site is part of the largest freshwater ecosystem in Africa, which is shared with neighbouring Republic of Congo. It also home to a high degree of biodiversity that includes such species as forest elephants, buffaloes, leopards and hippos as well as an estimated 150 species of fish and a wide variety of birds.

As of July 2008, nearly 168 million hectares have been designated for inclusion in the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance. Since I started working for WWF in May 1999, around 75% of the global area increase in hectares of the world’s Ramsar Sites has been the result of projects supported by WWF International’s freshwater programme.

But designation is not the end objective; it is just a first, but very important, step. I actually see it more as a powerful tool to get to the next step, which is to develop and improve the management and sustainable use of a wetland area and its natural resources. That is where the real success lies. Wetlands are not just about birds and fish, they are about complex and fragile systems that support nature and people. When wetlands are damaged or destroyed, it is not only wildlife that is at risk but also people.

You have been working on wetland issues for a long time. How did you get involved?

As a teenager growing up in Geneva, Switzerland, on the banks of the Rhône River and near Lake Leman, I became interested in waterbirds. Before going to school I used to go down to the lake at dawn and follow the migration of waders, terns, gulls, ducks and other birds. I also started taking part in a regular winter waterbird census. Through waterbirds I became interested in their wetland habitat. I think many people working in wetland conservation started out like me as avid birdwatchers.

Although I studied international relations at university (environmental studies didn’t really exist at that time), I never stopped being involved in nature conservation. In fact, starting in the late 1970s, I took part in a local campaign to restore and protect the Teppes de Verbois, a unique part of the Rhône River floodplain that is known for its diversity of birds, amphibians, reptiles, dragonflies, plants and just about everything else.

It was on this campaign that I learned just about all aspects of wetland management … and politics. One of my key responsibilities was to coordinate and negotiate with all sorts of stakeholders: landowners; farmers; construction firms; the gravel industry; fishermen associations; an electric company, which included managers of a nearby dam; local, cantonal and federal authorities; and other conservation organizations. All had different ideas and views on how to best use this riverine area. Initially, I had thought the campaign would last only 2-3 years but it took 25 years to get the 100-hectare area restored and protected. Ironically, it became part of a Ramsar-listed Site well before I started working closely with the Convention on Wetlands.

Another project that played an important role in how I became involved in wetland management was the construction of artificial floating islands on the Rhône River near Geneva to attract the Common Tern, which then was actually a very uncommon waterbird species in Switzerland. When I initiated the project back in 1979 most people thought I was crazy and that it would never work. Today, the islands host one of the largest tern colonies in Switzerland, and several local nature associations have successfully replicated the model elsewhere in the country.

The most important thing I learned from these early experiences is that you can have all the strategic plans and studies you want, but what you really need is patience and to be able to talk with and convince a lot of different people with different interests. This is equally true for protecting a relatively small area like the Teppes de Verbois or something as large as the Ngiri-Tumba-Maindombe.

Your commitment and efforts to wetland protection around the world has been recognized with the announcement that you are one of the winners of the Ramsar Wetland Conservation Award. What does winning this award mean to you and for your work?

This was a big surprise. Even better, it was officially announced to me on my birthday, which coincidentally falls on World Environment Day (5 June). This has been a wonderful birthday present. It has been amazing how many messages of congratulations I have received, some from people I don’t even know. Many colleagues I work with from throughout the world heard about me winning the award and were excited about what it means to our projects and future work.

On a personal level, the award is a tribute to all those who supported my interest in nature and wetlands conservation, especially Geneva ornithologist Paul Géroudet and Geneva naturalist and artist Robert Hainard, as well as my parents and my wife, Wendy Strahm.

On a professional level, the award represents recognition for all the work WWF has been doing globally in wetland conservation over the last decade or so. Like wetland conservation in general, this award is not about one person, but the result of teamwork. Hopefully, it will help us get the support we need - including the financial resources - to achieve even more results in the future. I also hope it serves as a call to those countries who need to accelerate progress on their wetland conservation efforts.

What does the future hold for you and wetland conservation?

In 2002, the Convention on Wetlands set a target to reach a global coverage of at least 250 million hectares of Wetlands of International Importance by 2010. While we are not quite there yet (as of July 2008 there were 1,758 Ramsar Sites, totaling nearly 168 million hectares), I believe this target can be achieved, but more realistically by 2015. This is provided that an intensity of efforts and investments similar to the ones achieved since 1999 can be pursued and sustained by then. I certainly have no plans to slow down and will keep working towards that goal.

I also believe it is important to expand the work of wetland conservation beyond the “traditional” wetland conservation community. By this I mean more engagement with regional governmental organizations (including international river basin commissions), bilateral and multilateral donor agencies, such as the GEF and regional development banks, and very importantly, the private sector. Only through a systematic approach using broad partnerships will we have a chance to succeed in our conservation efforts.

2011 will be a special year - the Convention on Wetlands will celebrate its 40th anniversary and WWF its 50th anniversary. Few people actually remember that WWF was founded in 1961 to support a wetland conservation project, a project that successfully led to saving the Coto Doñana wetlands in Spain, now a national park and Ramsar Site. Doñana is a symbol of the strong historical links between the Convention and WWF. I look forward to many more years of cooperation between the two organizations in the future.

-- Interview by Mark Schulman, former Managing Editor at WWF International