Recognition of Excellence 2002

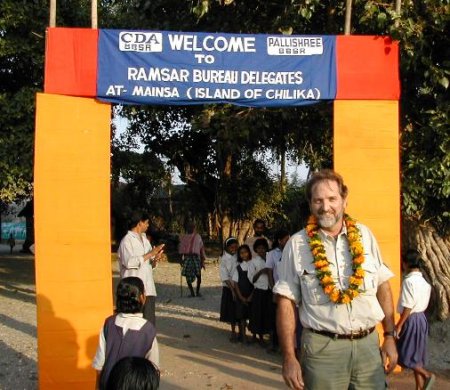

Dr Max Finlayson (Australia)

Dr Max Finlayson is being awarded a "Recognition of Excellence" for his scientific work and his commitment to wetland conservation, which have greatly contributed to the progress of wetland science and the work of the Convention, particularly the work of the Convention's Scientific and Technical Review Panel (STRP) throughout the 10 years since it was created.

Dr Finlayson has made outstanding contributions to the body of guidelines and recommendations available to the Contracting Parties to the Convention on Wetlands, particularly in the fields of wetland inventory, assessment, and monitoring. In these three areas, he has provided inspired leadership for the development, by the Ramsar STRP, of protocols and guidelines, formally adopted by the Conference of the Contracting Parties (COP), which are now used as standards throughout the world.

In particular, Dr Finlayson has contributed to the development of Ramsar wetland monitoring procedures, the procedure and guidelines for the operation of the Montreux Record (of Ramsar sites where changes in ecological character have occurred, are occurring, or are likely to occur), and the Convention's definitions of ecological character and change in ecological character.

In preparation of Ramsar COP7, Dr Finlayson led the development of the Global Review of Wetland Resources and Priorities for Wetland Inventory (GRoWI) which identified major gaps in baseline wetland inventory coverage. Over the past three years, he has led the STRP expert working groups on wetland inventory, ecological character, climate change, invasive species and dams, and has prepared several substantive reviews, guidance and draft Resolutions that will be considered by Ramsar COP8.

In Australia, Dr Finlayson has undertaken extensive programmes of wetland assessment and monitoring, notably with regard to the likely effects of uranium mining, and in relation to the impact of invasive species and climate change and sea-level rise. Similar analyses have been undertaken in other countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Dr Finlayson contributed to the establishment of the Mediterranean Wetlands Initiative (MedWet) which now operates under the aegis of the Convention. He has worked closely with Wetlands International, one of Ramsar's International Organization Partners, for many years; he has served on Wetlands International's Board of Directors and, in 2001, was elected its President.

Dr Finlayson is not only a highly respected and widely knowledgeable wetland scientist recognised worldwide for his inspiration and commitment to advancing wetland conservation and wise use in the field and through international mechanisms, he is also well known for his strong commitment to involving local communities and indigenous people in wetland wise use, and to ensuring improved understanding between scientists, managers and stakeholders.

The Recognition of Excellence of the Convention on Wetlands is given to Dr Finlayson in gratitude for his outstanding contribution to wetland science, conservation and wise use, and to the work of the Convention.

Newspaper Article by Peter Murphy, murphymedia@austarnet.com.au

Dr Max Finlayson, the Australian scientist who won a Recognition of Excellence in the Ramsar Wetland Conservation awards for 2002, has an unusual background for a man with a worldwide reputation as a practical, hands-on conservationist.

He was born and educated in Western Australia, one of the driest States in the driest nation/continent in the world. Yet Dr Finlayson has gone on to specialise in water quality and wetlands research in Europe, Africa, South East Asia and his home country, Australia.

And he built the scientific base for his research and conservation achievements while living and working for almost two decades in Jabiru, an isolated township built specifically to support uranium mining in the Alligator Rivers Region of Australia's Northern Territory.

Dr Finlayson is one of only two individual contributors to wetland science honoured with Recognitions of Excellence in the 2002 round of Ramsar awards. The other is Dr Monique Coulet, of France.

Dr Finlayson was singled out for Recognition for a professional lifetime of work which supports the Convention on Wetlands, and particularly in providing leadership for the work of the Convention's Scientific and Technical Review Panel over the past decade. The Ramsar citation mentions his work in establishing the Mediterranean Wetlands Initiative and contribution to Wetlands International, serving on its Board of Directors and currently as the organisation's newly elected President.

Born in Mount Barker, Western Australia, in 1954, Max Finlayson graduated with an honours degree in Science from the Botany Department of the University of WA in the State capital, Perth, in 1975. He then enrolled as a PhD student in the Botany Department of Townsville's James Cook University, in North Queensland on Australia's tropical East Coast. It was during this post-doctorate work that young Max had his first exposure to the mining industry and the politics of water usage.

His PhD project was investigation of the hydrobiology of the water supply system of Lake Moondarra, a man-made lake adjacent to one of the world's biggest copper, lead and zinc mines at Mount Isa, a 20,000 - strong mining community on Australia's inland desert fringe, some 1000 kilometres west of Townsville.

Lake Moondarra is a multi-purpose reservoir, created in mineral-rich country, with all the benefits and problems of a large body of water in a warm, arid area, adjacent to 20,000 people who love their swimming and recreational boating. The lake had the lot - nutrient run off, secondary treated sewerage effluent, water weed infestation, heavy metal accumulation and herbicide problem through efforts to control Salvinia, the worst of the noxious alien weeds.

The results of the three year investigation were adopted by the body managing the water supply and recreational uses of Lake Moondarra, and the project gave Max Finlayson his Doctorate of Philosophy in Botany, and a taste for the practical application of science. He also learned the importance of diplomacy when presenting scientific findings to water users and managers. These skills equipped the young scientist for his next role as a biologist with the Water Quality Council of Queensland, which involved investigating chemical and biological problems in waterways throughout the rapidly-developing South East of Queensland.

Dr Finlayson remembers that an emerging aspect of his workload at that time involved responding to the concerns of the general public about water quality and possible pollution. "It was a serious aspect of this work, and was addressed assiduously in an era when much scientific work was done in isolation from the general community," he said.

Which is the polite scientist's way of saying that up to the 1979/80 period in Australia, industry had generally stopped dumping everything from sump oil to mining residue in the nearest waterway, but environmental scientists still worked to their Government or industry employers, and there was little community involvement in the researching or reporting of environmental issues.

Dr Finlayson then moved to the fruit growing area around Griffith, New South Wales, as a limnologist working for the Division of Irrigation Research with Australia's premier scientific body, the CSIRO. He worked with small teams of ecologists and agronomists on projects as diverse as assessing the potential of native aquatic plants to treat noxious waste water, as well as environmental surveys of developing irrigation areas in other parts of Australia.

With his developing determination to see real outcomes from applied science, Dr Finlayson enjoyed the challenge of working with agronomists and agricultural technical officers, many of whom still regarded a wetland as "a bloody swamp" to use the Australian vernacular, and a good site for cropping once the land was drained.

"Making parallel judgements between functional parameters in wetlands and rice paddy was an interesting and, at times, an innovative challenge," Dr Max said. "At that time, limnology and wetland research was not given the emphasis that it has received in recent years. Thus, much of this work was undertaken with minimal support from national strategic sources, but was highly regarded overseas."

In the early 1980s, a renewed push for large-scale uranium mining in the Alligator Rivers Region of the Northern Territory became the unlikely catalyst for limnology and all aspects of wetlands science to suddenly lose its "boffin" status and become not only popular with the public, but also politically necessary to local and Federal Governments.

The uranium development boom came in the middle of enormous social and political change in North Australia. In 1976, the Federal Parliament in Canberra passed the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT), giving approximately 27,000 Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory the right to claim inalienable freehold title to vacant Crown land as well as vast areas of reserves, such as Arnhem Land. One of the first large tracts of country to be designated as Aboriginal land was the 21,000 square kilometres of river systems, bird-rich billabongs, majestic escarpment and coastal fringe known as the Alligator Rivers Region, now better known as Kakadu National Park.

Kakadu is home to more than just one of the world's great wetland ecosystems - it also has the vast Ranger and Jabiluka uranium deposits, which has made the area a touchstone for political and environmental controversy for the past quarter of a century.

Extraction leases had already been granted over these massive ore bodies, and there was considerable opposition to mining development. Over the previous couple of decades, uranium mining at Rum Jungle, also in the Territory's Top End, left a legacy of environmental damage which took five years and millions of dollars to rectify.

Because of the complexity of the legal, environmental and political issues involved with opening uranium mines on Aboriginal land in a newly-declared national park, Canberra commissioned a judicial inquiry into uranium mining under the direction of Mr Justice Fox of the Federal Court.

Justice Fox ruled that the mining leases could be worked subject to strict safeguards to prevent another Rum Jungle. Central to these safeguards would be the establishment of the Office of the Supervising Scientist, a Federal authority based at the new mining town of Jabiru in Kakadu National Park, with extensive resources to undertake research into the effects of all aspects of uranium mining and processing on Kakadu, particularly its river systems and wetlands.

It was a huge scientific task, fraught with political, administrative and cross-cultural peril. On the domestic and international stage, there was an upsurge of opposition to uranium mining, particularly in a national park, and lots of armchair scientific experts were keen to catch out the new Supervising Scientist in an environmental mistake, however minor. There were cross-cultural difficulties because of the park's ownership, leaseback arrangement and status as a tourism icon, which sees more international visitors in Kakadu each year than the entire area sustained in a century of normal habitation by its traditional owners, the Aboriginal hunter-gatherers.

The Australian nation had never faced such a challenge - operating a major uranium mine in the middle of a national park with the world's biggest wetlands systems, home to a huge variety of wildlife, some of it, such as the giant estuarine crocodile, with lethal habits. The park's wetland and river systems are watered by the Asian monsoon, which follows the virtual drought of the dry season from April to October with torrential rainfall, dumping up to nine metres of water on the Territory's Top End in the five months of the Wet season.

Suddenly, scientists with good degrees, wetland experience and people skills belonged to a profession whose time had come! In 1983, Dr Finlayson was recruited from the CSIRO to work as a plant ecologist at the Alligator Rivers Region Research Institute, otherwise known as the Office of the Supervising Scientist.

The scientists had to start from scratch. "I had to document species diversity, biomass and seasonal fluctuation of the flora of the Alligator Rivers Region, which included the two million hectares of Kakadu Park, and to research the botanical aspects of the heavy metal and radionuclide balance of the region," Dr Max remembers. Due to pressure to establish criteria for water release from uranium mines in the region, my activities were primarily directed towards the ecology of the seasonally inundated grasslands and paperbark (Melaleuca) forests that comprise the Magela Creek floodplain.

"This area was relatively unknown to scientists, so I had to undertake both baseline and functional ecological studies. And as weed infestations became more prevalent in the national park and on the mining leases, I organised a comprehensive survey of weed species in the region. Additionally, I regularly provided advice to the National Park Authority on the management and control of several wetland weeds."

During this time of intense scientific work matched by intense interaction with the park's managers, traditional owners and major users, the uranium miners and tourist operators, Dr Max had plenty of opportunity to practice the community consultation that he recognised as a major plank in any conservation endeavour from previous professional experience.

"You can have all the scientific baseline data and financial support in the world, but unless the local community, which uses that ecosystem for food, shelter or recreation is fully involved in the conservation effort, it will eventually fail.

"The only people with any real knowledge of the Kakadu environment were the Aboriginal traditional owners, so earning their trust and taking their advice was central to the scientific task at hand, and had the added bonus of saving us all a lot of time."

After six years at Jabiru, Dr Finlayson wanted to move out of wetland sciences and work in wetland conservation. That opportunity presented itself in the form of a three-year contract as Assistant Director and inaugural Head of Wetlands at the International Waterfowl and Wetlands Research Bureau, Slimbridge, United Kingdom, which is now part of Wetlands International.

As there was no coordinated wetland management program in place, Dr Finlayson again started from scratch - developing a network of wetland contacts, establishing wetland training courses, organising workshops and symposia, and all the time collaborating closely with the Bureau of the Ramsar Wetland Convention.

This led to a broadening of Dr Finlayson's international network, through hands-on projects and advisory briefs in Uganda, Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean Basin and New Zealand. He is particularly proud of his involvement, in an advisory capacity, in the $AU30 million, 10 year restoration of Sweden's bird lake, Hornborga, and the development of wetland conservation strategies for the Mediterranean and the Volga Delta in Russia. .

As well as honing his scientific skills and experience in wetland research and restoration, Dr Finlayson gave flesh and blood to his twin doctrines of conservation and sustainable development of wetland resources through local community consultation and involvement.

"In this light I received invitations to contribute to workshops in Spain, Australia, Russia, Sweden, Italy, USA and Czechoslovakia on wetland management and policy," Dr Finlayson said. He also surveyed potential threats from mining to an important wetland site in South Africa, which combined wetlands expertise, knowledge of mining rehabilitation and revegetation issues, all carried out in a highly-charged political-economic arena --- much like the situation back in Kakadu!

The three years of working out of a European base built up Dr Finlayson's international network and profile, and gave him renewed zeal to ensure that science made itself more relevant by taking into account the political and economic consequences of major scientific decisions. After exploring these broader horizons, Dr Finlayson felt he was ready for a return to wetland science and came back to Jabiru in 1992, where he is now the Darwin-based Director of the Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist. He is also President of Wetlands International and Director of the National Centre for Tropical Wetland Research, which involves the Northern Territory University as well as the James Cook University in Townsville and the University of Western Australia, where Dr Finlayson began his distinguished career.

The difficulty in profiling the life and times of Dr Finlayson is the sheer volume of published works, page-long lists of major projects in a dozen different countries, and a travel schedule which belongs in the world of international diplomacy.

Dr Michael Storrs, wetlands adviser with the Northern Land Council, who has known and worked with Max Finlayson for 20 years, explains it this way; "He is an extraordinary networker. He keeps in touch with all the people he meets on his travels, swapping information and comparing notes.

"So it is never just a trip in isolation to deliver a lecture or advise on a project - his contacts and networking skills return the value of that trip many times over. And Max is very happy to live his work - he is happiest wading through a wetland somewhere in the world when he is on holidays. His wife is an ornithologist, so professional life and recreational pursuits are complementary." Dr Storrs said.

Another long-term associate of Dr Finlayson is Mr Simon Nash, the Netherlands-based CEO of Wetlands International, who points out that there is a bon vivant side to Dr Finlayson's personality.

"He promoted wetland work in the Volga Delta at a time of great social change in Russia. Since becoming the President of Wetlands International, he is heavily involved in the implementation of our new, science driven strategy, and promoting wetlands issues within other international initiatives and agreements.

"His current interests centre on developing procedures for wetland inventory, assessment and monitoring, as well as climate change. As usual, he encourages maximum involvement of local communities in wetland programs. He is a good "people" person.

"Max played a key role in organising the groundbreaking 1991 Grado Mediterranean Wetlands Conference which led to the birth of MedWet - one of the first regionally-based wetland conservation initiatives," Mr Nash said. "The conference was plagued by freezing temperatures, but through a combination of dry wit and an Australian love of red wine, he won over the conference, which succeeded in creating the momentum for MedWet.

"He met his wife in Grado, too!"

Dr Finlayson says the biggest challenge facing science is communication. "To achieve scientific goals, scientists must be effective communicators, and that means being so good at communication that the general public want to listen," Dr Finlayson said.

He practices what he preaches by putting the highest priority on working through local communities and individuals, a constant theme of his harangues (mostly polite) to his scientific colleagues.

"It is the applied use of the scientific findings of myself and my colleagues which matters most, and that is where I am lucky with my scientific base built up in a number of countries, and the support of the Supervising Scientist for the maintenance of that base, and all other aspects of my work.

"The scientific base developed at the Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist is now a well-qualified tool to support and help guide national and international initiatives, principles and research-the ultimate practical application of scientific findings."

"Max Finalyson's great breath of expert knowledge and understanding about wetland conservation and wise use, and his commitment applying this to help countries worldwide, is outstanding" says Dr Nick Davidson, Deputy Secretary General of the Convention on Wetlands. "His work as a member of the Convention's Scientific and Technical Review Panel over the last 10 years has been pivotal in preparing a significant number of the technical guidelines in the 'toolkit' of Wise Use Handbooks now being used by our member countries to guide their efforts to secure sustainable wetlands."

Dr Finlayson has seen a lot of changes in the world of wetland science that he first entered at Lake Moondarra in 1976, and they are mostly for the better. He has no regard for the mystique of the ivory tower of science ---his creed is all about practical applications and communication with people. He regards the Recognition as a culmination of a professional lifetime spent bridging the gap between science and people --- with the outcome of helping those people manage their environment. And he recognises that the task is far from over - wetlands and wetlands managers still need plenty of assistance.

The awards and Recognitions, together with the Evian special Prize, will be presented to the winners during the opening ceremony of the Conference of the 132 Ramsar member countries on 18 November this year in Valencia, Spain.